Here’s a new interview in culturenow.com with yours truly – which gives a good background on how and why we came to make this film and all the joy and pain in doing so!

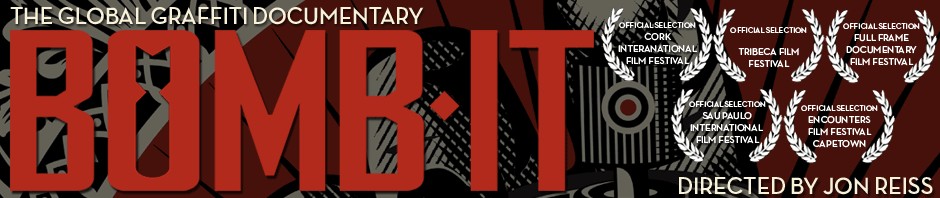

Writing It Everywhere An Interview with Bomb It Director Jon Reiss by Samantha Skinazi

raffiti, bombing, ugly crime, beautiful crime, street art, outsider art, painting, tagging, social protest. Whatever you call it Bomb It director and producer Jon Reiss says that “it really is a hot topic for a lot of mainstream folks.” Reiss, named by Daily Variety as one of “10 digital directors to watch” calls graffiti “the ultimate outsider art.” And defines it as: “Any form of illicit artistic interference in public space.

raffiti, bombing, ugly crime, beautiful crime, street art, outsider art, painting, tagging, social protest. Whatever you call it Bomb It director and producer Jon Reiss says that “it really is a hot topic for a lot of mainstream folks.” Reiss, named by Daily Variety as one of “10 digital directors to watch” calls graffiti “the ultimate outsider art.” And defines it as: “Any form of illicit artistic interference in public space.

When I arrive for our interview I find him hard at work in his Brentwood, California home office, wearing khaki shorts and a well-worn Obama t-shirt displaying the word “HOPE.” He has been working on Bomb It for the last four years. And it seems he’s still working on it. An excess of brilliant footage will eventually translate into six geographically divided documentaries (São Paulo, Japan, New York and L.A. among them).

Having grown up in “pretty whitewashed suburbs,” Reiss’ relationship to graffiti in his youth was admittedly, “None at all.” His earliest awareness of the movement “was the punk rock anarchy symbol, and the graffiti that punk rockers were doing in the late 70s and 80s.” Documenting punk bands like The Dead Kennedys and The Circle Jerks served as Reiss’ initiation into the world of documentary filmmaking. From his early days creating videos of Survival Research Labs’ dangerous performances to his 1999 rave culture documentary, “Better Living Through Circuitry,” Reiss has remained well-versed in the language of sub-cultures.

Bomb It, his latest project, began by chance one night at a dinner party when Reiss was asked to pitch on a narrative film about graffiti. Some preliminary interviews in New York with writers like Sharp and 2ESAE revealed to Reiss the depth and potential of graffiti culture as a subject for an extensive and expansive documentary film.

Reiss half-jokingly compares the process of creating Bomb It to that of a mad scientist who slowly realizes he’s halfway through creating Frankenstein’s monster: “But you keep on at it. And then you’ve got this monster and it’s like you’ve got to feed it and deal with it.”

Here’s what Dr. Frankenstein had to say on the subject of his beautiful and insightful monster:

Kode and Kenor paint for Bomb It, Barcelona

Samantha:

You begin the film with a quote from Goethe’s Poetry and Truth, published in 1811: “I was, after the fashion of humanity, in love with my name, and, as young educated people commonly do, I wrote it everywhere.” What does this mean to you in relation to the evolution of graffiti youth culture?

Jon:

Hopefully it changes people’s frame of reference from the get-go. At least people who know who Goethe is – which I can tell you not everyone gets that unfortunately. But at least they get the 1811 reference. And for me one of the first things that inspired me about doing the documentary is that this has been going on for thousands of years. Essentially as KRS One said, “since the birth of human consciousness.” And you can do all the enforcement in the world, but it’s not going to go away. It’s not going to go away because people need to do it. There’s some weird need to state that I exist, some biological thing that causes people to want to state their existence. I love seeing the film with a crowd who knows who Goethe is, because it always gets a chuckle. And it helps open them up to what they’re going to see. You see that quote and you think it’s going to be some graffiti writer from the 70s or the 80s – and it’s Goethe from 1811.

Samantha:

Did your ideas about graffiti and/or consumer culture change as a result of your experience?

Jon:

Yeah, definitely. I never thought about graffiti in relationship to advertising before I made the film and heard the arguments for it. I always was very aware of how public space is used, and very concerned about why people can create a city like Los Angeles, which is kind of mess as a city. It’s not really a city – it’s like a big suburb with some urban aspects to it. I’ve always been a fan of Mike Davis. But I never thought of graffiti in that context. Also, in the beginning we were only going to do big beautiful murals. We were really inspired by Dame, and some of the stuff you see around L.A., and by OS Gemeos [from São Paulo]. We weren’t even going to deal with tags. Because, [I thought] tags are ugly, and that’s not even what our film was about. It just shows how little I knew about graffiti when I started making the film.

That lasted like five or six months. The first thing was that I soon learned how integral tags were to the whole culture. And then, what took a little more time, a couple years, is that now I actually appreciate a nice tag with good hand style, as much, or more than a piece that’s taken a couple days. A lot of times when they’re overdone they kind of have the life sucked out of them. They don’t have that kind of urgency and immediacy.

Samantha:

The romance of graffiti permeates so much of your film: The sound of spray cans against the still night, the explosion of color onto drab surfaces and the rush that comes with transgressing social rules. Would you describe what it felt like to follow all of this?

Jon:

Yeah, it’s pretty exciting. It reminded me of my youth [we both laugh], my near youth I should say. You understand part of the allure. And you understand why writers say if it were legal they probably wouldn’t do it. Because then it wouldn’t be something they’d have to do sneaking around and breaking the law. It would be like “Oh, I can go do this in the daylight? Well I’m gonna go do something else.” You still would have people doing it in the daylight. Look at the amazing art they have in Barcelona. Those are people just painting for hours. Can you imagine if you had people spending hours doing murals on the sides of the freeway? And just leave it up, and you’d have endless beautiful murals. You know people would say, “Oh who gives them the right?” Who gave someone else the right to put the big ugly freeway wall there? Obviously, we did as citizens. But is it that horrible to allow that impulse to beautify something to happen? You know the problem for most people is that graffiti is so associated for them with tags and blight.

DJ Lady Tribe at work in Los Angeles

Samantha:

You mentioned Barcelona and the free walls in Spain. Why not in the States?

Jon:

Because the States has a completely different attitude about graffiti, which is that all graffiti is bad graffiti. Look, you can’t even get free walls in cities in the United States, and you have to battle for every square inch. Los Angeles only has the three small walls on Venice Beach that constantly get painted and repainted and repainted. There are some not officially sanctioned walls. There are places where people can go paint if they’re savvy and stuff will stay up….But those are more in the worst parts of town where what already exists is so ugly anyway. Parts of town that are similar to São Paulo, third world countries where they’re happy to have any coat of paint on a wall.

So it just won’t exist here until there’s an attitude shift. And hopefully the film can contribute to that somewhat. You know it’s a problem and it comes out of the whole quality of life [argument]. It kind of stems from New York enforcement, like when we tried to do an event in New York City for the film opening at the Tribeca Film Festival. We had a bar that said, “Yes paint our outside wall, we’re totally happy with it.” We even said we would paint it over the next day. But the local council nixed it. And this is in the Lower East Side. Nixed it under the guise of “any graffiti is bad graffiti.”

Samantha:

There seems to be this national tendency to always place the beginning of art and social movements in the East. Do you feel like there’s an argument to be made that graffiti started in L.A. in the 50s and 60s as opposed to Philidelphia in the late 60s?

Jon:

Yeah, I think so. And the whole historicity of it is all kind of a joke anyway. Even Cornbread says there was a guy writing up his name on freeways before he was doing what he was doing, although he doesn’t remember the guy’s name. We did a fair amount of research and we couldn’t find any sort of reference to it. The hobos were doing it on freight cars at the turn of the century. We have plenty of examples of other graffiti in Los Angeles from hobos or otherwise that was going on in the 20s and 30s as well, outside of Chicano culture. So there are all kinds of historical antecedents. As Goethe said, he wrote his name everywhere and he was doing it for fame. I like to think the film calls into question all notions of who started it.

Samantha:

For me, the interviews with law enforcement agencies sort of fell flat. It was a noble effort, but they all sounded similar. Comparing their scripted-sounding moralizing arguments to the range and complexity of the writers’ positions, the anti-graffiti camp seemed to be dealing in much more simplistic modes of thinking.

Jon:

No, I mean. Well. I don’t think…

Samantha:

You didn’t feel that way?

Jon:

Well to an extent that’s somewhat true. But on the other hand, like Valerie Hill’s whole marketing strategy. Yes, there’s a certain didactic kind of fervency to them all. And part of what we were showing is that this is all around the world. But I thought it was important to show the other side. To give out their reasons as much as possible, to give some indication of the broken window theory and what that is. But I think also towards the end with Valerie Hall and her whole marketing idea, equating Hershey’s candy with anti-graffiti. That’s pretty different, funny. And Oscar Goodman…

Samantha:

I’m not sure which is worse for kids though.

Jon:

Exactly, that’s kind of the point. And Oscar Goodman saying they should cut off the thumbs of graffiti writers. Non-enforcement people, like Joe Connelly is quite different form anyone else. He’s so over the top – guerrilla buffing! And also that guy Russ Kingston who we don’t identify by name in the piece. He’s got some pretty thoughtful arguments about it. There is something to be said for that point of view. Someone comes up and paints your car. I mean that’s kind of fucked up. Graffiti writers should frankly be pissed off about it too. That doesn’t do much for their graffiti movement to have some people just fucking up people’s personal property.

Samantha:

Some of them expressed that, saying, it’s just stupid to write on someone’s house.

Jon:

Yeah, I know. That’s why we say that. You have to understand the other side, I think, to help you promote your own side. Hence one of the reasons Barack is so wonderful [smiles]. I knew I was going to bring Obama in here somehow.

Tracy Wares films Sixe in Barcelona

Samantha:

Some of the artists and writers make repeated references to being street soldiers, and to being engaged in a war. The heading above the film’s title on the cover of your DVD reads: “Street art is revolution.” Your film also touches upon the ways by which the street art style has been co-opted by the very consumer culture against which it’s rebelling. Why did you choose the metaphor of revolution?

Jon:

Because I think on one level it is a revolution of visual public space. It’s not going to turn over any governments or anything like that. Although it has been used for that. And I think part of the historical use of graffiti has been for political protest.

Samantha:

Like in Capetown.

Jon:

Not just in Capetown, but in São Paulo. The Pixadors started as an anti-dictatorship street movement. There’s famous graffiti form Florence in the Medici era. And it was used in street protests in Roman times. So people forget that it’s a form of free speech. Even though the free speech at times is artistic, it’s still free speech. Like if you think of the Pixadors now in Brazil, that part of the reason they come into the city and do their graffiti is so people know they exist and don’t forget about them. Or the kids from the projects in Paris that come in and paint up the city. It’s like [saying], “Things are still fucked up and we’re here. It’s not all nice beautiful lovely place for you guys to live in, and screw us over.” Whether that’s revolutionary or not is maybe up for debate. But I think there is some relevance in that.

I think another way to think about it is that revolution doesn’t have to always be political. It doesn’t always have to be something that results in overthrow of governments. Revolution can also be the way that you view the world. One of the things that I hope we’re achieving with the documentary is to get people to look at the world around them in a different way.

Samantha:

I think it does achieve that.

Jon:

And from talking to people it seems like it does. And to me that’s a revolution. That’s almost a revolutionary concept. You know at core, at the very end of the film, it really calls into question property ownership. Like why do business people – certainly there are building codes, but why can in Los Angeles someone just build the ugliest strip mall? But then the kid comes along and paints that and he’s thrown in jail? How come the guys who build the ugly strip mall aren’t thrown in jail? I think they’re creating as much or more urban blight than graffiti writers are.

Obey – Shepard Fairey

Samantha:

The artists and writers really address the reality that globally money buys the rights to control visual culture in public spaces.

Jon:

Which is going to become a much bigger problem. It already is. You can already spend the day going to the gas station, watching ads at the gas station. Going to the bathroom, seeing ads in the bathroom. They’re already making it so you’re credit card is tagged with your personality. So that when you swipe your card at the supermarket the ads targeted towards you will pop up.

Samantha:

So does someone with the capital to buy billboard space have more of an inalienable right to control visual landscape?

Jon:

I don’t think so, but our culture thinks so. The dirty little secret is that in Los Angeles 10% of billboards are illegal. That didn’t make it into the film, but I like to talk about it in interviews. And it will probably be in the subsequent follow-up documentaries. Especially when you see the [billboards] that are draped onto building walls. Those are nearly all illegal, like those huge things on Highland. You know those big Apple billboards? Those are not legal.

Samantha:

And nobody minds. No one’s going to enforce it.

Jon:

No one is going to enforce it. I think people maybe mind, but it’s just sort of accepted. No one says, “Oh what’s that billboard doing there? There’s no license number on that billboard.” And the whole legality of billboards is such bullshit. From what I’ve heard in Germany, they actually do pay a fair amount of money, and that goes to public services. So you have a billboard up and maybe you pay 10,000 bucks a year to the city, or $100,000 a year to the city for big ones or video ads. [Here,] they pay 35 bucks a year for the right to have a billboard. 35 bucks! And part of the reason the Billboard Lobbying Association keeps it so low is, A, because they’d have to pay. But, B, if there were more money, there’d be more money to fund an enforcement agency and they don’t want to be policed. So if they only charge 35 bucks, there’s barely enough to hire one person to monitor billboard activity in Los Angeles or any big city. It’s shocking.

Samantha:

I wanted to bring up Jacques Derrida, just for fun.

Jon:

Sure, I never understand him too well. I’ve read him, but let’s see if you bring up something that…makes sense.

Samantha:

He once said that Deconstruction could be thought of as “a gesture that does not naturalize what is not natural.” I think these can also be called gestures of refusal. Your film deconstructs the idea that graffiti is thoughtless and ugly and always leads to violence. The artists and writers refuse to accept commonplace rules that say money and authority control public space. Do you think Bomb It can be characterized as a gesture of refusal?

Jon:

I would say all my documentaries have that as an element. I like to say that they have more than that. Jill [my wife] would complain that I haven’t got beyond that punk rock refusist [mentality]. You know that I haven’t moved beyond that in a sense.

Samantha:

Where is there to move beyond that?

Jon:

Well, [laughs] ask her. But you know, there’s one thing to refuse, and there’s another thing to construct. I think one of the things that’s interesting about graffiti is it does both. Some just refuses. Bad tagging for me aesthetically, bad tagging is merely kind of a refusing thing. But good tagging and good street work and good graffiti to me aesthetically does more than refuse. It’s constructive. It actually enhances the urban environment.

Samantha:

I think there’s a tendency to attach that pejorative idea to deconstruction or refusal, thinking that somehow it just means sticking your nose in a corner and saying, “I’m not doing anything else.”

Jon:

Well you said it. You said that deconstruction was a refusal. I don’t think it’s just that. I think there’s more layers to it than that. But I’m just going off what you said.

Reiss films Nunca in Sao Paulo

Samantha:

When I say refusal, I guess what I mean is that every refusal refuses a particular thing, and then accepts new and other things. It’s a refusal of certain values.

Jon:

Yeah, for me, there’s a certain thread through all of my doc work. Most of my docs deal with sub-cultures. It is a group of people who in that sense are refusing to participate in the way of life that modern society has prescribed for them. So they’re forming their own structures, and they’re forming their own social networks. And creating a world for themselves outside of the world that society has laid out. That was very important to me. I became a filmmaker because of that, because of punk rock, and because of what punk rock provided to me.

Samantha:

How about in terms of how some of these writers and artists sustain themselves economically? Is that fair to ask? What does Cornbread do?

Jon:

Struggles. And that’s what I’d like to get in [the follow-up films]. Like T-Kid paints homeless shelters for the city of New York. He doesn’t paint them with graffiti; he paints them with a roller and white paint. He’s a union painter for the city of New York. Everyone thinks these guys are so rich and blah blah blah – it’s just not really true.

Samantha:

How would you articulate or conceptualize the differences between American street art and the international work? To guide the question, is there something more brazen, or rock and roll, or maybe I should say gangsta – like something of the cowboy that still lingers, in the American work versus the international?

Jon:

Yeah I think that’s true. Certainly there’s a lot more personal injury done to writer on writer here than the rest of the world. Like in New York, the crews, people would beat each other up over turf. Turf meaning if someone went over someone’s work. It was a lot more of a physical scene. In L.A., there’s been recent issues with the whole tag-banging thing where there are writers killing other writers, which is totally stupid. And that’s pretty unique, unfortunately. But, you know, hey it’s the United States. I would say we’re one of the most violent cultures on earth, so why would the world of graffiti be any different?

There’s also pretty amazing stuff going on here. I don’t want to say that’s the only thing that distinguishes the United States from other countries. It’s a pretty international movement now, so stuff spreads like wildfire across the Internet. You have people like the Graffiti Research Lab who are doing pretty interesting things in New York with various technological innovations in terms of graffiti…It’s hard to say if there’s that much difference stylistically going on in the States. But I think part of that’s because the U.S. style, or the New York style, has been so pervasive or influential around the world.

Samantha:

There seems to be this unspoken idea, like with drugs, that any non-moralizing discussion of illegal activities encourages the proliferation of those activities.

Jon:

I mean that’s what you were saying in terms of free walls earlier, in terms of giving access.

Samantha:

Has your film induced a graffiti epidemic yet?

Jon:

I’m not going to answer that. I heard there…[stops himself]. I’m not going to answer that, not going to answer that [laughs].

One Response to Jon Reiss Interview in culturenow.com